I love a good conversation, and Enea from Adoratorio Studio is not only a great conversationalist but also someone whose vision—together with business partner Camilla Zampolini—has shaped one of Italy’s most renowned digital studios over the past decade. I must admit, we could have talked much longer, but I feel we covered a lot of valuable ground in our nearly one-hour discussion. We decided to conduct the interview in Italian, but to help our international audience, here is a fully edited and cleaned transcript of our conversation.

Today I’m delighted to welcome Enea Rossi of Adoratorio. For anyone who has spent the last fifteen years in a fallout shelter, Adoratorio is a major player in the industry I belong to. I don’t want to flatter anyone, but he’s someone I truly enjoy talking with, work aside. We’ve met at various conventions, and I’d like to focus on topics that are closer to our line of work. So, welcome, Enea, and thank you for being here.

I also appreciate that you carved out some time for us. Because of geographical distance and our busy schedules, crossing paths isn’t easy, so having you here makes the moment even more special. You and Camilla Zampolini founded Adoratorio. How long has the studio been active now?

Thanks, Fulvio, and hello to everyone watching. It’s a pleasure to see you again. We usually meet in person, so meeting online is almost a first. Adoratorio officially opened on 17 March 2014, though the first traces go back to July–August 2013, when we were still figuring out what we were going to do. So yes, after twelve years we could call ourselves veterans.

When we started I was 28 years old; now I’m approaching 40 and realise I’m the oldest person in the studio. I enjoy that, because it keeps me connected with younger people and the changes they bring. That connection across generations is an opportunity my parents never had.

I often say I’ve felt 40 since I was 18! I call it “benevolent fatherliness”: having lived through the Flash era as a freelancer, I see similar cycles repeating in younger eyes and it feels tender. For instance, I no longer write code; after years of doing it, everyone in my company is happier that I’ve stopped. I imagine your role has changed a lot at Adoratorio too. What did you actually do at the very beginning?

At the start I literally “made graphics.” I designed brand assets, catalogues, websites; I handled invoices, met the accountant, emailed clients, even posted on social media—everything. Camilla mirrored that multitasking, and we had two interns from my teaching stint at Brescia University. I’m a self-taught graphic designer who gradually evolved into a designer and creative director.

Our first Adoratorio jobs came from a freelance client I could no longer handle alone: we had to create a brand, a catalogue, a website, even a custom configurator. Camilla brought in a wine brand from Lake Garda that paid us in €5 vouchers—we literally cashed them at the bank! Looking back, ten-plus years isn’t that much time, but so much has happened and our roles have naturally evolved.

Nowadays I rarely design. My task is to safeguard the vision—our own and the client’s—so that every project balances values, culture, innovation and brand identity.

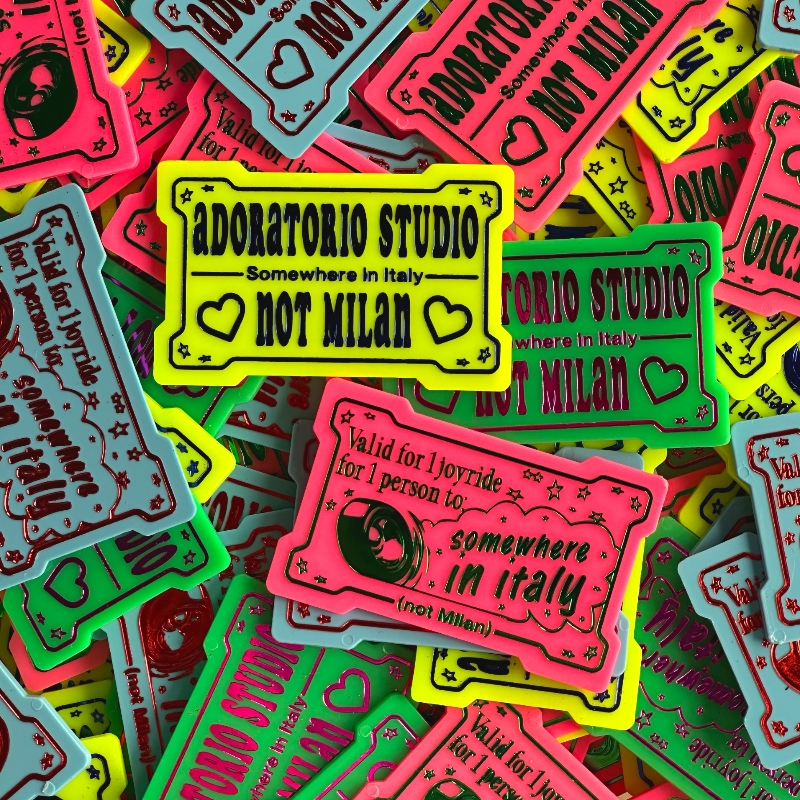

“Not Milan” teaser and fiches

That authorial dimension is obvious in your work: every Adoratorio project has its signature. I also loved your “Not Milan” positioning; being from Udine, closer to Munich than Milan, I get it. I assume it was both a market and spiritual choice.

Exactly. We happened to be born in Brescia, not in a global hub. “Not Milan” began almost as a declaration of independence—gentle, not hostile. People in other provincial cities love it because it validates the idea that creativity isn’t confined to the centre. International clients would ask, “Are you from Milan?” and we’d answer, “No, Brescia—30 minutes away.” For an American that’s practically the same city!

We’ve always wanted to stay a studio, not a big agency, so the slogan also signals scale and humility. Opening in Amsterdam, on the other hand, was a long-standing dream. The city’s size, culture and pace fit how Adoratorio lives and works. We aim to grow personally and culturally, not merely in headcount. Amsterdam offers the right projects and relationships without the big-city frenzy.

I feel the same. For me Munich is more appealing than Milan because it’s built on “old money”—established companies with depth. Even talking to their quiet owners is invigorating. Amsterdam would be the city I’d move to if I left Udine; Boston gives me a similar, human-scaled vibe.

Human connection is indeed the central value of our era. It’s harder in smaller cities but still possible—and vital—to nurture meaningful ties. That’s why we invest time in Amsterdam: conferences led to friendships, which led to opportunities. We take things slowly and let them fit us. Finding office space there is tricky, but we’ve given ourselves two years; patience lets ideas digest and mature.

We share the urge to give back locally. For instance, we restored an ’80s arcade cabinet and installed a tongue-in-cheek “Fricoman” Pac-Man clone in Friulian dialect at a community fair. Kids crowded around a machine objectively worse than any phone game, but the shared experience thrilled them.

Exactly. Quality time and lasting experiences are what matter. Technology itself is never the goal; it’s an enabler. We adopted WebGL, 3-D and physical installations because they served clear strategies and emotions, not because they were trendy. Flash died, but its spirit—rich interactive experiences—has returned under other names. The tool may die; the drive to move people endures.

We recently finished our most emotional project to date—artistic, social, interactive. I’ll share the link as soon as it’s public. It lets visitors participate, not merely observe. That participatory layer is the evolution of everything we have tried to do on screens.

And technology should always serve a purpose. I’m not anti-AI, but without discipline infinite scrolling burns the brain: 7 200 dopamine hits in three hours! There’s no creativity without boredom; we need off-screen time. My team isn’t allowed to read email after five p.m.

I used to work from seven in the morning till two at night; now I disconnect at weekends and encourage the studio to do the same. Downtime replenishes energy and sharpens judgement. My wife is a psychotherapist and works only three days a week so she can process what she has heard on the other two—creatives need similar sedimentation.

I believe “sustainability” in digital isn’t about how green a site is but how long the experience lasts in someone’s memory. Slowing users down enough to feel—that’s almost revolutionary today. Our recent COP 21 project took a dry report and turned it into an immersive story about a changing planet; it deliberately asked visitors to linger.

Exactly. I consider my greatest professional win the fact that I shut my laptop at five and have no computer at home. Off-screen life enriches on-screen work.

Taking care of ourselves means taking care of others. When we created “Child of Time” for our anniversary—a seat-based installation that printed a thermal-paper snapshot of your emotional state—the ink was meant to fade, just like the feeling itself. Those physical-digital hybrids are our long-term artistic pursuit, and that’s why Camilla once said her dream is to see an Adoratorio piece at the MoMA.

A beautiful ambition. When I saw Refik Anadol’s gigantic real-time data sculpture at the MoMA I wept; the technology was breathtaking but the tactile impact moved me. Camilla’s wish isn’t about prestige—it’s about embedding a new form of design into cultural heritage.

Exactly. If one of our works ended up there, it would mean it mattered to society, not just won awards. The physical location is secondary; what counts is what stays inside us—the “inner museum.” Still, yes, I share Camilla’s dream: seeing our installation in the MoMA would show that digital storytelling can be culturally significant.

As the rapper Neffa said, “Ideas are big or small according to the heads that contain them.”

That feels like the perfect closing thought.

Thank you, Enea, for this wonderful conversation. We’ll meet again soon.

Thank you, Fulvio. I hope this was good, valuable time for everyone. Until next time!